Picky Eater Solutions: Making Mealtime Fun and Nutritious

Identifying the Root Causes of Picky Eating

Understanding the Underlying Issues

Pinpointing the root causes of selective eating habits demands careful observation. Parents often notice their children develop strong preferences or aversions to certain foods during early childhood. Tracking these patterns over time reveals valuable insights into potential sensory sensitivities or developmental factors. Keeping a detailed food diary helps identify which textures, colors, or flavors consistently trigger resistance.

Environmental influences play a significant role in shaping eating behaviors. The atmosphere during mealtimes, parental reactions to food refusal, and even subtle peer pressure at school can all contribute to selective eating patterns. Recognizing these external factors allows for more targeted interventions that address the whole context rather than just the food itself.

Examining Sensory Processing

Many children with selective eating habits experience differences in how they process sensory information. Certain textures may feel uncomfortable, while strong smells might overwhelm their senses. This isn't simply stubbornness - their nervous systems may genuinely struggle with particular food characteristics.

Occupational therapists specializing in feeding issues often identify specific sensory profiles. Some children demonstrate hypersensitivity to crunchy textures, while others avoid slippery or mixed-consistency foods. Understanding these individual sensory thresholds helps tailor food introductions more effectively.

Assessing Oral Motor Development

Chewing and swallowing difficulties sometimes underlie selective eating behaviors. Children who experienced early feeding challenges or developmental delays may still struggle with certain food textures. Undetected oral motor weaknesses can make eating some foods genuinely difficult, leading children to avoid them altogether.

Speech-language pathologists can evaluate chewing patterns, tongue movement, and swallowing coordination. When these skills develop atypically, children often self-limit to foods they can manage comfortably, creating the appearance of pickiness when it's actually a motor challenge.

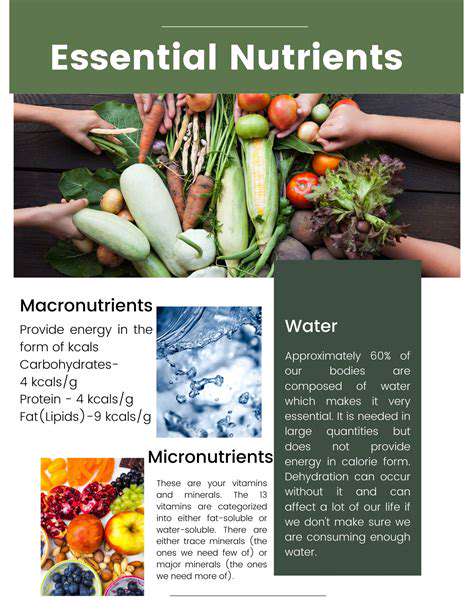

Considering Medical Factors

Various medical conditions can contribute to selective eating. Gastrointestinal discomfort, food allergies, or acid reflux may cause children to associate certain foods with pain. Even after the medical issue resolves, the negative association often persists.

Nutritional deficiencies can also influence food preferences. For example, zinc deficiency sometimes leads to decreased appetite and altered taste perception. A thorough medical evaluation helps rule out these underlying contributors before assuming the behavior is purely behavioral.

Introducing New Foods Gradually and Playfully

Creating Positive Food Experiences

The key to expanding a child's food repertoire lies in making exploration enjoyable. Rather than framing new foods as obligations, transform them into discoveries. Present unfamiliar items alongside trusted favorites, creating a safety net of known quantities. This balanced approach reduces anxiety while encouraging curiosity.

Portion size matters tremendously when introducing novel items. A single green bean on the plate feels far less intimidating than a full serving. Over multiple exposures, gradually increase the amount as comfort grows. This incremental method respects the child's pace while systematically building acceptance.

Engaging Multiple Senses

Children learn about food through all their senses long before tasting. Encourage them to describe a food's color, shape, and texture with their fingers first. Smelling new items helps prepare their brains for the flavor experience to come. This multisensory introduction creates familiarity that often leads to eventual tasting.

Creative presentation makes unfamiliar foods more approachable. Arrange vegetables into funny faces or use cookie cutters to create interesting shapes. When food becomes play, resistance often melts away. The goal isn't deception but rather making the exploration process engaging.

Modeling Enthusiastic Eating

Children closely observe how adults interact with food. When parents visibly enjoy a variety of foods, children naturally become more curious. Make positive comments about flavors and textures during meals. This modeling teaches that food exploration is both normal and rewarding.

Family-style meals where everyone serves themselves provide powerful learning opportunities. Watching others take portions of different foods demonstrates variety as the norm. Even if the child doesn't initially participate, this exposure lays important groundwork.

Creating a Positive Mealtime Environment

Establishing Predictable Routines

Consistent meal and snack times create security that supports adventurous eating. When children know food will be available at predictable intervals, they feel less pressure to eat large quantities at any single meal. This regularity reduces anxiety-driven food refusal.

Simple pre-meal rituals signal the transition to eating time. Washing hands together, setting the table, or saying a thankful phrase all help shift focus to the meal. These predictable patterns create psychological readiness for the eating experience.

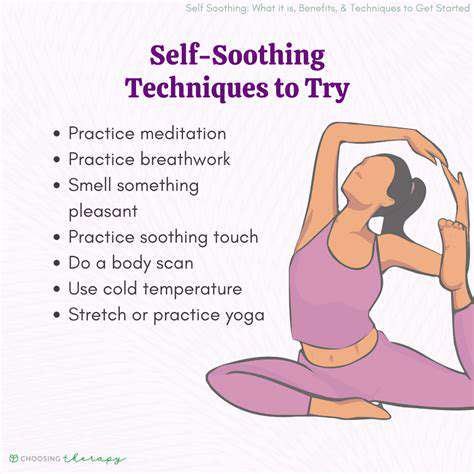

Minimizing Mealtime Stress

Power struggles over food often backfire, creating negative associations. Instead of demanding certain foods be eaten, focus on creating a pleasant atmosphere. Interesting conversation, appropriate humor, and genuine connection make the table an inviting place.

Avoid using dessert as a bargaining chip. This approach artificially elevates sweets while framing other foods as obstacles. Instead, include small portions of preferred foods at every meal, ensuring the child always finds something acceptable while being exposed to variety.

Respecting Individual Differences

Children's appetites fluctuate naturally from day to day. Forcing a child to eat when not hungry or restricting when genuinely hungry can disrupt their natural hunger cues. Trusting a child's internal regulation fosters long-term healthy eating patterns.

Temperament also influences eating behaviors. Some children approach new foods eagerly, while others need multiple exposures before feeling comfortable. Recognizing these personality differences prevents mislabeling normal caution as problematic pickiness.

Making Healthy Choices Fun and Appealing

Celebrating Food Adventures

Frame trying new foods as an exciting exploration rather than a chore. Create a food passport where children get stickers for sampling items from different food groups or cultural traditions. This gamification approach taps into children's natural love of achievement.

Farmer's markets and u-pick farms provide wonderful opportunities for food education. Seeing where food grows and meeting the people who produce it creates meaningful connections. Children often feel proud to try foods they helped select or harvest themselves.

Creative Food Preparation

Simple kitchen tasks give children ownership over their food choices. Washing vegetables, tearing lettuce, or stirring ingredients all provide low-pressure exposure. As skills develop, they can graduate to more complex tasks, building confidence along with culinary ability.

Themed meals add an element of fun to nutrition education. A rainbow day where every color gets represented, or an around the world night featuring different cuisines, makes learning about variety exciting rather than didactic.

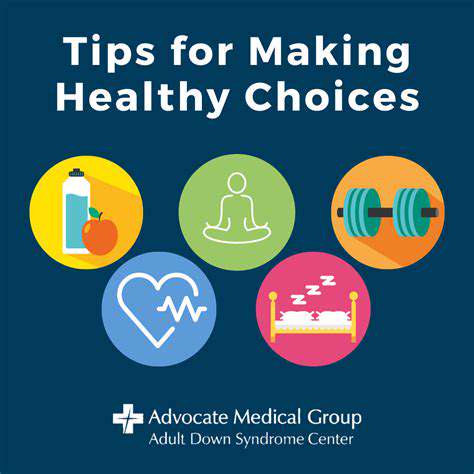

Balancing Nutrition and Joy

Healthy eating shouldn't mean deprivation. Including enjoyable foods in moderation prevents the development of forbidden fruit syndrome. When no foods are completely off-limits, children learn to self-regulate rather than binge when opportunities arise.

The most effective nutrition education happens through positive experiences rather than lectures. When children associate healthy foods with pleasure and discovery, those preferences often last a lifetime. The goal isn't perfection but progress toward a varied, balanced relationship with food.